There is so much reflection and thought to write under this title, and the last. I will apologize now for the incohesive and random nature of my thought process and my failure of ability to express in words what you can only understand from experience.

I have been in Africa now for a month and a half – living, studying, and experiencing. Many people like to just leave it at that, but I like to be more specific. I was in the West African country of Ghana. A country with a relatively stable country and economy (some crises right now: electricity and fuel), full of culture and tradition, and even in its immense ‘development,’ Ghana remains with disparities like any other country – even the US. Africa is not a monolithic mass in the southern hemisphere of the world. So many people would rather chalk up the continent into one idea after reading, hearing, or experiencing a small aspect. Intellectuals, non-intellectuals, those who are from Africa, those who haven’t, and so many experts would rather clump the continent together. That just can’t be done. There is nothing about Africa as a whole that can sum up what it is. It is just like how in the US each state has its own special customs or accents or scenery – Africa as a continent is the same, but better. So many people would rather save time and refer to Africa as a monolithic mass. However, as I lived, traveled, and experienced Ghana the falsity of this idea was all too evident. Our MSU study abroad group was based in Accra, the capital city of Ghana and did much of our work at the University of Ghana. We took many field trips: Cape Coast, Volta Region, Kumasi, Villages near Danfa, and more. Every time that we would leave for a trip the Ghanaians that helped us would tell us that we would experience something so different from what we had seen before; something that we could only have seen in our dreams. They could not have prepared us more. Each region that we visited, each city, town, or village that we stayed in was completely different. We witnessed the many ethnic groups of Ghana, their music, traditions, and customs – the Akan of the Accra area, the Ewe of the Eastern Volta Region, the Asante of Ashanti Region. . . If there were so many differences and experiences in one of the smaller African countries, than what does that say for the massive continent itself?

One of the most obvious differences between Ghana and living in the US was the notion of time. In the States it is very hustle, bustle, go, go, go, exuding impatience – but in Ghana things will happen when they do. You can go for a meal order your drink, wait a bit, get your drink and order food, wait sometimes two hours (tops), get your food, and leave in about three hours from your dinner excursion. But its ok, what else were you going to do? Enjoy your food take your time, chat with your tablemates, tell jokes, enjoy the scenery, people watch – everything will happen in good time. I like that notion of time. I liked it so much that I stopped wearing my watch and often had to ask a Ghanaian with a cell phone for the time. I am not a rushed person, well at least not as rushed as most, and I like to take things as they come. Time should not be such a definitive aspect of your life. Time should work for you. One Ghanaian told me, “Here, we are manufacturers of time.” As opposed to we, in the States, who are the slave labourers to time. I return and time is back in my face again, cracking the whip. The ubiquitous tyrant of everyone’s lives will remain to be the arbitration of time.

Hurtling down the road at breakneck speed, I look over at the speedometer – hoping that we don’t nail a pedestrain or hawker – I see that the speedometer has been put out of commission, figures, they don’t want to know how fast they are going themselves. A mass of traffic appears and we, amazingly, stop in time to not die. The traffic lights have decided to work today. The car exhaust and black smoke flow into my front seat window as the hawkers walk by selling apples, ball floats, candy, posters, you name it. They are accompanied by those crippled by polio, beggars, and blind men walking with an aid. This is the taxi ride of Accra, you have not experienced Accra if you do not ride in the front seat of a taxi. Now back in the States I enjoy always smooth roads, no traffic backups (I don’t live in a very big city), and no death-defying driving skills. That is a fun little part of each day that I will miss.

We all take our health for granted. Everyone. In Ghana many of the students got sick, had diarreha, fever, something – back home we are rarely sick, we are rarely decommissioned for a day, we are rarely at odds with the world we live in as far as our health is concerned. I have the luck of owning an adaptable body and did not get sick in any regard. Thankfully whenever I travel nothing affects my internal health. The sun likes to affect my external health – my nose is still red with sunburn. We take our health for granted. Our professor who worked for over two years in the Peace Corps said she was always sick and while in Ghana I noticed this as well. Many people have fever, coughs, malaria, and who knows what. . . but, depending on location and class, they could not self medicate from the cabinet or see a doctor right away. They walk to get clean water, no faucet in the kitchen with clean water. We take our health for granted. I thought about this often when a group of us would go running. We would draw quite a crowd and get some cheers from school children. They must have all thought we were crazy – running miles in the hot sun at a fast pace, did we want to die? Well no, we Americans enjoy exercise, but for the Ghanaians we encountered and many Africans exercise is a way of life not a luxury to feel good. Will we ever stop taking our health for granted?

One of the sad reflections from Ghana is the idea of culture and tradition that is just not seen in the US. Ghanaians have a deep shared history and strong traditions rooted in their respective communities, which share much in common. There is a huge importance of family and the customs that are passed down. Many professions are passed from father to son, mother to daughter and the day to day of family life is passed down through traditions. In each of the villages we visited we were sure to make courtesy calls to all the local chiefs. The local chiefs still hold a great deal of power and we soon understood the protocol for visiting a chief. The importance of connections between people is huge. In some cases this cause corruption and nepotism, but there is an underlying good intention. Your connections with family are extremely important and you never lose that connection no matter what – if you decide to blow of family then you are looked down upon. You keep the family name, you name your children for past relatives, you visit often, and if you have a good paying job, you send support. This unknown emphasis on human connection is amazing. It goes beyond family to the people you meet in life. I couldn’t believe how many people could remember my name from a one time meeting. It must be the greeting ritual that makes it easier to remember. In Ghana you do not just wave and say, “Hi, how are you?” and receive the standard response, “Fine, thanks.” You stop talk, inquire about family, friends, and life. The nature of people in Ghana is just so much more cohesive and happy. I think it is because of the emphasis on people and getting to know them.

One of my favorite parts of Accra is that the grocery store is right at your vehicle window. While you are stuck in the mass of rush hour (sometimes it isn’t even rush hour) traffic, hawkers walk up and down the rows of cars, trucks, lorries, and taxis selling just about anything. Probably the oddest things I saw being sold were: a pair of puppies, toothpaste, a box of chickens, coffee mugs, umbrellas, the list goes on and on – pretty much anything that up might need is right outside your window. Besides the window side store and clubbing scene, I prefer to stay out of the big city. My best experiences on the etire trip were in the small villages of Otinibi and Danfa. The village life is so much more appealing and friendly. The village is a more closely knit community and is extremely welcoming.

Ghana was an amazing experience from all of the great classwork we did and, most of all, from the excursions we took as a group and adventures on our own. Meeting people was my favorite part and learning about their lives was most interesting. I don’t think I could have had a better experience in Ghana, unless maybe I spoke the language, but I am getting there. Ghana is an amazing place, an interesting beacon for the continent, and a force to be reconned with in the future of our global economy. I still have some very specific reflections from Ghana, so be sure to check back to learn about: investing in death, the discovery of oil in Ghana, and the confusion of the rastafaria movement.

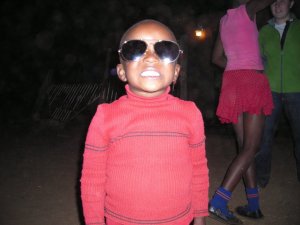

Here are some random, artistic, super random pictures left over from Ghana:

Downtown Osu at night, Osu has many western style establishments that are run mostly by Lebanese.

An awesome tree at the Forex by the Center for Art and Culture.

The arc of Ghanaian independence just down the road from the presidential palace.

A fisherman’s association from the view of Cape Coast Castle.

A fisher and his boats taking a rest in the nook of Cape Coast Castle.

The canopy of Kakum National Forest, beautiful!

Don’t look down (from one of the canopy platforms.

Slightly frightening sign in Accra, just before we sped off. . .

This is the village area we stayed in, Shiashie, engulfed by the growing Accra.

The moon between palm trees at our hostel on Don’s 21st birthday.

A nice village scene in the Volta Region near Wli Falls, tallest in West Africa.

HIV/AIDS awareness and education.

Cool coke bottle shot, drink up.

At the University of Ghana.

One of our favorite restaurants to visit, off the beaten path, but well worth a good Ghanaian meal.

Me and Joseph, the most amazing hostel worker ever.

Index of blog post series on Ghana.