Obesity is still on the rise. In many cities there have been decade-long campaigns to improve healthy food access, spread information about health risks, and new national efforts to get children active – are they not working? Latest estimates predict that by 2030 almost half the adult population will be obese. Recently, the CEO of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) wrote in the Washington Post about their latest report and the future impact of obesity on our economy. She noted the decline of productivity and increasing health care costs associated with obesity. While we often think about fast food, inactivity, and individual choices related to being obese, how often do we consider the economic causes and effects?

Obesity is Not a Choice

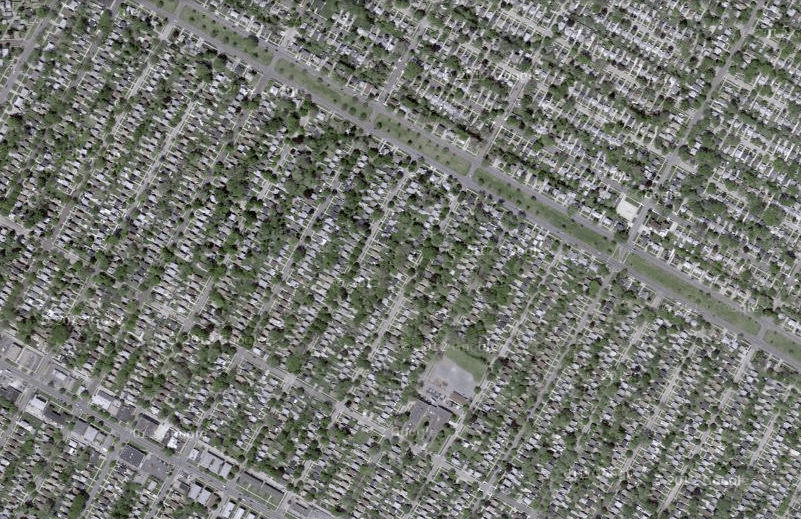

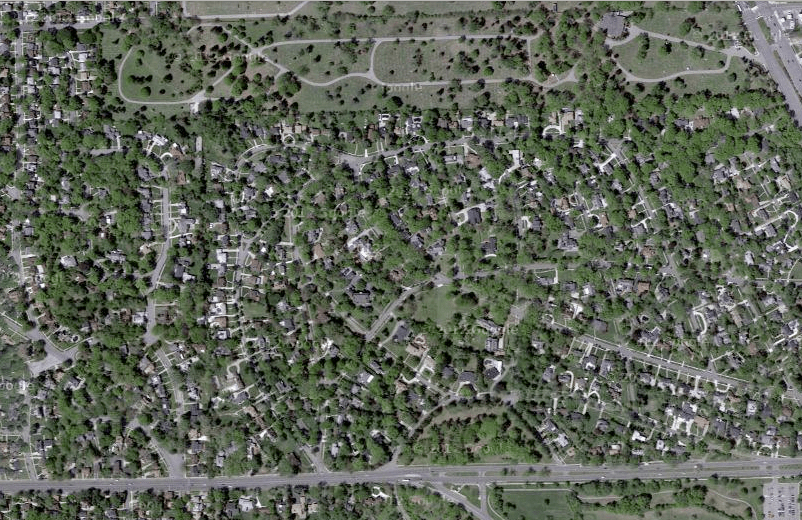

I have never met anyone who said that they specifically chose to suffer the health effects of being obese because they thought it would be a great way to live. However, beyond personal choices, obesity can be correlated with a number of social and environmental factors, namely: poverty, urban areas, as well as minority and low-income populations.

Just as individuals cannot choose their parents, they also cannot choose their life circumstances, which unfortunately can sometimes hinder efforts to live a healthier lifestyle. Research has shown that rising rates of obesity disproportionately affect Black and Hispanic populations. This demonstrates a confluence of factors with roots in racially motivated housing policies, lack of social mobility due to historical discrimination, and the absence of adequate health services for these communities.

Impoverished communities are filled with companies looking to take advantage of the marketplace of poverty. Dollar menus, frozen dinners, and corner store snacks – not to mention the advertising which helps build a psychological belief that it is quicker and cheaper to eat unhealthy foods.

In short, obesity is just as much an economic reality as it is a need for healthier lifestyles. It represents a by-product of mass producing foods to reduce costs and increase profits. People do not choose to live in poverty nor do they choose to be obese. Economic constraints on top of fast food advertising drives a culture of unhealthy eating.

Tax the Fat

The debates have raged about recent plans to tax the size of soda pop in New York City or in other countries the tax on fatty foods. There is a growing field of research on behavioral economics, which argues that people will choose the option that is most beneficial to themselves.

This is, however, not always true. People do not always make the most rational decision especially when it comes to their food and eating habits. Increasing the economic burden on people who typically choose unhealthy foods is not necessarily the best option. If a tax is placed on high-calorie or high fat foods it allows the food and beverage companies to continue avoiding responsibility. It isn’t about personal freedom, it is about being able to compete in a marketplace where the cards are constantly stacked against the poor.

Food and beverage companies will still find a cheap way to produce their products that works around any tax or restrictive policy. These companies have a primary goal to make a profit. If making that profit means burdening the population with unhealthy foods and the long-term health effects, they have no qualms. This is where people generally argue that it is about personal choice. This is partly true, but also relates to my first argument that you can’t always choose your life circumstances. All around the world now people are struggling with obesity and healthy eating. Food and beverage corporations are able to take advantage of global income and food disparities to generate their profits.

Behaviors Always Win

Using a “fat tax” to increase the economic difficulty of buying unhealthy food is doing no good when there is a psychological war on TV and advertising campaigns.

“It’s the behavior stupid!”

We can talk all day about the responsibilities that corporations have to give people healthy foods as well as the responsibility of individuals to keep themselves healthy, but in the end it all comes down to behavior. When I say behavior I’m talking about the eating habits that people have learned since their childhood, the behavior influenced by the food commercials seen on TV, the behavior informed by the massive portion-sized, “give me what I paid for” food culture.

When we are constantly bombarded by images of juicy burgers, steaming pizzas, and actors telling us how amazing it is to get quick, cheap food – we will eventually believe it. Food and beverage companies employ their own teams of psychologists to be able to manipulate their advertising to be the most convincing. These companies have found out the best ways to exploit the disparities that people face in order to get more people to buy their unhealthy foods. Don’t have time to make dinner? Bring your kid through the drive-through. Buying groceries on a budget? Get 3 for $5 cases of pop or 2 for $5 bags of potato chips.

When it all comes down to what will or won’t work, people need to understand what they are up against, they need to be informed on what foods will benefit their health, and they also need to be able to have the tools to make healthy lifestyle changes. While many food companies watch their profits grow, many individuals watch their weight grow due to their own economic disparities. Helping people address these learned behaviors and economic barriers will help to reduce health care spending and increase the productivity of our economy.